The Convict Poet

There, reckless of the mighty storm, that rages round his manly form, a convict mournful stood.

This story contains references to suicide. If you are struggling and need to talk to someone, please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636.

On Christmas Eve in 1825, in Yelden, in the county of Bedfordshire, Thomas and Rachel Walker welcomed the birth of their son, Charles. He was christened according to their Protestant faith, with his birth later registered at Dr Williams’s Library in London.

His parents both likely benefited from the Harpur Trust, which was established in 1566 by William Harpur to support the education of poor children at Bedford Grammar School. Both Thomas and Rachel were literate. When he reached school age, they enrolled Charles to begin his studies.

By age 15, in 1841, Charles was one of two bakers’ apprentices living with baker Favell Barringer on St Cuthbert’s Street in Bedford. He was said to have worked for Favell for three years before becoming a soldier. Throwing doubt on his supposed military career, there were questions as to how he was able to receive a discharge.

Charles eventually returned to Bedford, and in the first quarter of 1846, he married a local woman, Ellen Waller. At the time of their marriage, she was pregnant. She gave birth to their son, Charles Maynard Walker, on 23 March 1846.

The family lived together on Priory Street in Bedford. Charles earned his living as a hawker, which took him away from home for months at a time. He also enjoyed writing and specifically wrote poems, having published a small collection of his work about “moral and religious subjects.”

The couple were known to have possessed some “valuable property.” How they managed to afford it became the subject of gossip. Charles claimed that he received an inheritance from a relative. His explanation did nothing to quell the rumours. On 22 June 1850, in an effort to stop the talk, he placed an advertisement in the Bedford Times offering a reward for information and threatening to prosecute anyone spreading “slanderous reports affecting his character.”

As it sometimes turns out, where there is smoke, there is fire.

On 10 July 1849, Charles Wells was sentenced to ten years’ transportation for multiple burglaries carried out in the villages of Frogmore, Ayot St Peter, and Hunsdon in Hertfordshire. He committed them accompanied by a man named Charley Watford, whom he had met at a lodging house.

Wells was apologetic and expressed remorse for what he had done. He provided Inspector Robert Dunn with a description of Watford, who dutifully wrote it down. The police continued investigating without much luck until 18 September 1850.

In the evening, on that day, Inspector Dunn was walking through Hartham when he noticed a man matching Wells’s description. He followed him to the railway station, then into the Albion pub. Convinced he had the right man, he arrested him and searched him. He found a screwdriver, a partially used candle, a box of matches, a map of Huntingdonshire, and a hawker’s licence in the name of ‘Charles Walker.’

Positive identification was paramount. Several days later, Inspector Dunn took Charles to the hulks at Woolwich, where Wells was being held. In a room in the dockyard, with seven other people in attendance, he asked Wells if there was anyone in his presence whom he recognised. Wells pointed at Charles.

Charles was held in the Hertford County Gaol while he awaited trial. By all appearances, he was “tranquil” and resigned to his fate. His visible behaviour disguised his internal desperation to escape the situation he was in.

At 1:45 am on 19 January 1851, Officer Henry Hollingdale was on night duty at the gaol and was doing his rounds. He heard a noise in the ward where prisoners awaiting trial were held. He inspected the area but saw nothing of concern. Rather than discount it, he alerted the gaol’s governor, Samuel Hatchard, and other officers, who got out of bed to investigate.

They examined the exterior of each door carefully and noticed that at Charles’s, the trap through which they passed food was not closed properly. They unlocked the cell and entered to find Charles fully dressed and standing by the door. He was holding a handmade skeleton key constructed out of a piece of old iron wire wrapped with a cotton cravat to increase its bulk. Reports indicated that it was quite skilfully made.

The implement was fashioned with great dexterity, and was an admirable imitation of the key of the cells, at which the prisoner could only furtively have glanced on some occasion when visited by the officers of the gaol.

With the use of a string, Charles had been holding the trap open and reaching his hand through it in an attempt to unlock the door using his skeleton key. The noise Hollingdale heard was assumed to have been the trap accidentally slamming heavily.

The officers searched his cell and also found a rope that Charles had constructed using stockings, a towel, and a cravat. While his attempt at escape was frustrated, the reporter noted that had he succeeded, he likely would have faced other difficulties. As punishment and to prevent another occurrence, Charles was stripped and moved to a different cell.

On 26 February 1851, Charles appeared at the Hertford Lent Assizes charged with stealing various items from the home of Reverend Edwin Prodgers at Ayot St Peter.

Reverend Prodgers recalled the night of 20 April 1849. He went to bed at 11 pm, and as was his habit, he ensured that the drawing room door was locked on the outside and the external door fastened. He was awoken at 7 am with the news that someone had broken in. The drawing room was in disarray, and his French clock, a concertina box, a silver inkstand, a gold penholder, and various coins and medals were gone.

Charles Wells, who had previously pleaded guilty to a similar charge, gave evidence against Charles. He first met him at a lodging house on 20 April 1849. After talking for a while, they went for a walk.

Wells confided in Charles that he had no money and was determined to get some. Charles was in the same predicament. He showed Wells some diamond rings, and after first lying about how he got them, he admitted that they were stolen. He was planning other burglaries and had ‘spotted’ a house that he was going to break into that night. He gave Wells the opportunity to join him, and Wells accepted.

They arrived at Reverend Prodgers’ house at about midnight and waited until one of the two candles they could see was extinguished. They broke open the grating, Charles entered on his own, and he let Wells in through the drawing room window. They took all the items that Reverend Prodgers had previously listed as stolen.

Wells and Charles locked the door on the inside, and when they were some distance away from the property, they broke open the concertina box. They tried smashing open the clock to take the inner workings but were unable to. They dumped it in a field and walked to Welwyn, Hertford, and then Ware. Days later, they committed another robbery.

Wells was in company with Charles for about ten days. He eventually pledged the concertina box and sold the silver inkstand, as well as other items, to Barnett Isaacs of the Blue Anchor on Petticoat Lane in London’s east.

The medals stolen from Reverend Prodgers were particularly identifiable, with one of them showing an image of a Chinese junk ship. Mary Ann Vyner was a servant at the Coachmakers’ Arms in Hertford. She remembered Inspector Dunn coming in and telling him that Charles had shown her a diamond ring as well as the medals on 21 April 1849 (the day after the robbery). She asked if she could have one, but he threw them away into a field. When shown the medals in court, she thought they were the same ones.

Charles Inch worked for the man who owned the field near the Coachmakers’ Arms. On 26 April 1849, he was walking through it when he came across four medals, including one with the image of a Chinese junk ship on it. He gave them to his employer, who gave them back to him the next day. Mr Inch gave them to his mother, but one was accidentally lost.

John Connor was a lodger at the Coachmakers’ Arms in April 1849 and saw Charles and Wells together. Charles showed him the medals and then a diamond ring, asking if he would like to buy it. His reason for selling was that they were short of money. John refused. When he was shown the medals in court, he recognised the one with the image of a Chinese junk ship on it.

George Hanscombe owned a lodging house at Bishops Stortford, and James Miller was a lodger there. Both men testified to seeing Charles and Wells together at the lodging house on 22 April 1849.

Mr Hawkins represented Charles. He dismissed Wells’s evidence as unreliable. He argued that the witnesses proved that Charles and Wells were in each other’s company after the burglary, but there was no evidence to show they were in each other’s company before. He also touched upon the medals and questioned whether a thief would be “openly exhibiting the proceeds of a robbery on the morning after its commission.”

He called witnesses from Bedford who testified as to Charles’s character. John Dennier was a grocer who had known Charles for about six years. He lived nearby and considered his character and conduct to be “perfectly straightforward.”

Jane Whitehead was a baker, and she knew that Charles worked as a hawker. She considered him respectable, but despite knowing him for eight years, she had no idea what he sold and never actually saw him sell anything.

George Payne was a plumber and glazier who had known Charles for five years. He had never heard anything negative about his character. Upon cross-examination, he admitted that, like Jane, he never saw Charles hawking anything. He really only knew Charles as a customer when he came into his shop for squares of glass and paint.

Judge Lord Campbell summed up the case for the jury and drew attention to the corroborative evidence that the prosecution had produced. Each witness’s story matched in some way to another. Charles’s witnesses were not compelling, and he left it up to the jury to decide “whether the corroborative testimony was sufficiently strong to enable them to rely upon the evidence of Wells.” After a short deliberation, they found Charles guilty.

Lord Campbell agreed with their decision and passed comment upon the fact that the crime was once a capital offense. He expressed concern that “the mitigation of the punishment” may have resulted in an increase in such offences. Despite his disapproval, he nevertheless passed the sentence.

The law, however, still provides a grave punishment, and it becomes my duty to pronounce that penalty upon you. The sentence is that you be transported beyond the seas for the term of fourteen years.

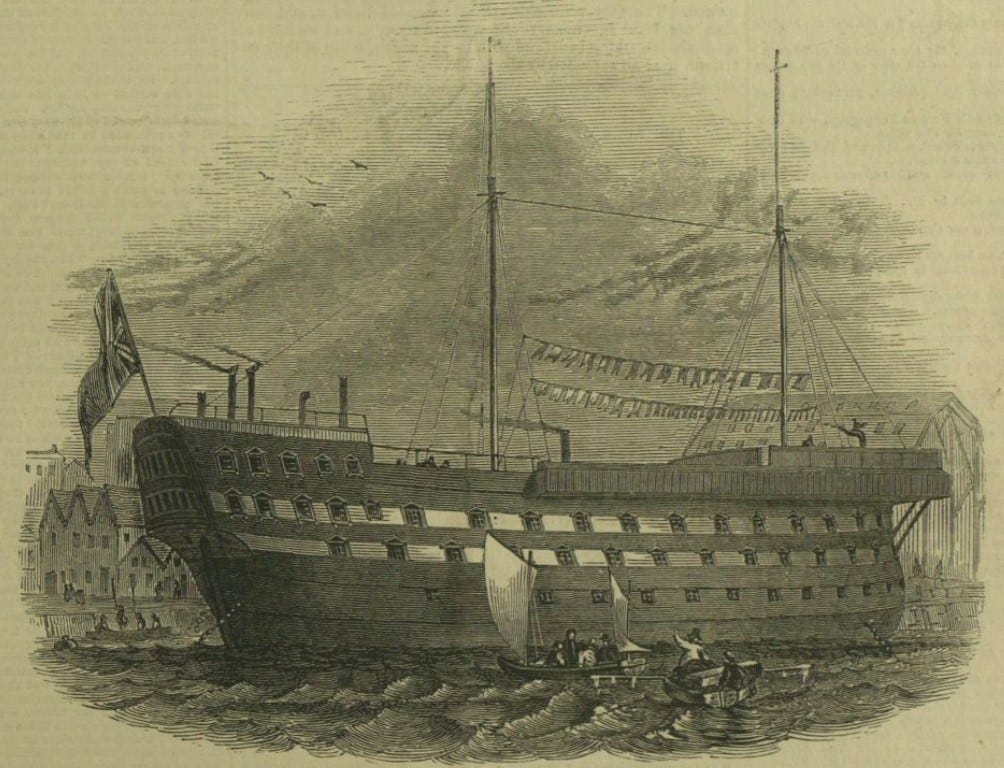

When the 1851 England Census was carried out on 30 March, Charles was still listed as a prisoner in the Hertford County Gaol. He was eventually removed, and for the next year, he was incarcerated on the ‘Warrior’ hulk on the Thames. It was not until 17 April 1852, that he boarded the ship ‘William Jardine.’ On 3 May, along with 211 other male convicts, he departed England for Western Australia.

The ‘William Jardine’ arrived at Fremantle on 1 August 1852 after a journey of 88 days. Disembarkation began on August 4th. Charles remained on board until the 5th, when he and the rest of the prisoners were taken ashore and marched to either the second or third division of the convict establishment. Upon being processed by the authorities, he was assigned as convict number 1364.

While land was designated for the future Fremantle Prison, the prison itself did not yet exist. Convicts, including Charles, were kept on premises at Fremantle leased from the Harbour Master. They spent their days quarrying stone and constructing the building that would eventually incarcerate thousands of future prisoners.

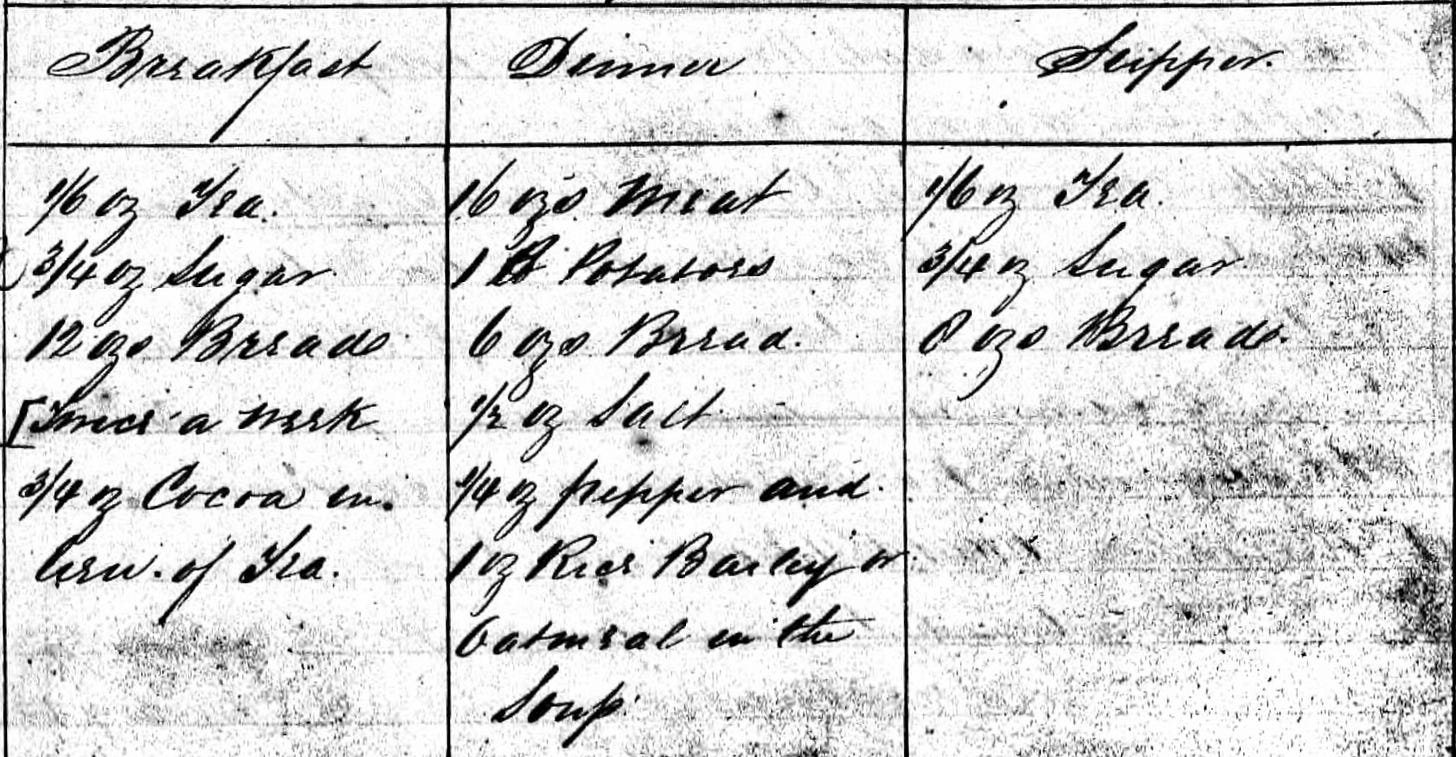

For Charles, it was a life of routine and bells. Warders would signal when it was time to get up (5 am), have breakfast (8:10 am), break for lunch (12:10 pm), eat their evening meal (6:10 pm), and go to bed (8 pm). Food was rationed according to scales set at various times in the year.

Charles was immediately put to work within the grounds of the prison establishment. By 25 October 1853, he was sent to the Guildford Depot and was designated a constable. Such an appointment only came about if a convict exhibited ‘exemplary’ behaviour. He was required to help warders with their duties as well as assist with discipline. His new position came with added benefits, but he was also expected to act in a certain manner.

They are enjoined to exhibit an example of cheerful obedience, propriety of demeanor, cleanliness, and good order to their fellow prisoners; using respectful language in conveying instructions, and carefully avoiding harshness, or domineering assumption, when in manner or language, in all intercourse with them. [15 December 1853]

On 22 March 1854, Charles was granted a Ticket of Leave, which enabled him to seek his own employment. He returned to his trade, with George Marfleet employing him as a baker in Perth.

For the most part, his behaviour was considered ‘good.’ He exhibited some signs of flightiness, but it was never serious. He was writing poetry again, and his lyrical verses and songs were proving popular. In October 1855, he offered his services to people who were interested.

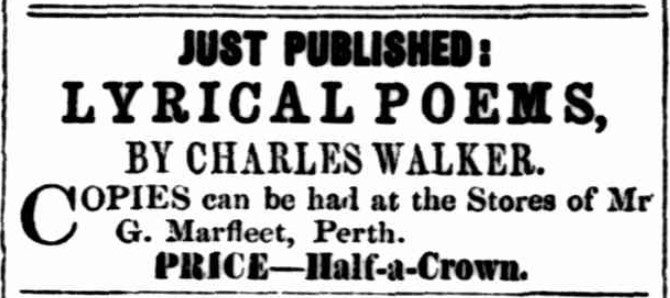

By the end of the year, he was advertising that he would be publishing a book of “lyrical and other poems.” On 6 February 1856, he announced that the book had been published. Copies were available at George Marfleet’s stores in Perth for the cost of half a crown.

Despite such positive events, things started to go awry in April 1856. He advertised that his manuscript was taken away from him in October 1854 and that he believed it “to be in the possession of some person well acquainted with its contents.” He offered a reward of £2 for its recovery. On the same page, he paid for a notice to be printed in The Inquirer and Commercial News in the form of a poem.

It is clear he was accusing a “tall chap” of spreading stories, and his poem was a warning that he should stop. Something was bothering Charles, and it may have caused him to neglect his duties.

On 16 June 1856, Charles was arrested and sent back to the convict establishment at Fremantle. He had absconded from work and was out of his district without a pass. He was sentenced to twelve months hard labour. As per the requirements set out in the Superintendent’s Orders book on 26 November 1855, as a reconvicted prisoner, he was placed in “separate confinement.”

Forbidden from talking to anyone, the extreme punishment was to continue for a quarter of his sentence. One can only assume that it was meant to be a deterrent for future poor behaviour once prisoners were released on a ticket of leave. Having experienced solitary confinement, perhaps officials hoped it would ensure that they would not end up there again. For Charles, it had a detrimental effect.

Just over a month into his punishment, at 10:30 am on 30 July, Charles died by suicide. He was buried the next day at 9 am. Unlike other convict deaths by natural causes, there was no one officiating at his graveside.

Charles Walker, the convict poet. He was another cog in the system whose ending was simply a dated entry in a book. Only a reporter from The Inquirer and Commercial News paid some kind of tribute to him. They described him as a “conspicuous character” who had a “tendency to insanity.” He had a “rage for verse making,” with his poems printed in the advertising columns of their paper. They also pointed out that he had written “a small volume entitled ‘Lyrical Poems,’ published some six months since.”

Charles’s story does not end with his death. The statements relating to his published works are intriguing. What became of them? There was one (aforementioned) attributable poem printed in the newspaper as a ‘notice,’ but were there any others? Did he publish a book of poems that would have been the first of its kind in Western Australia?

Searching for poetry in the newspapers is unfortunately not as easy as entering the word ‘poem’ in the search box on Trove. Instead, I skimmed through every edition from 1854 to 1856, looking for the tell-tale format of a poem. Many I saw were reprints from the journal ‘Punch.’ Two appeared to be reader-submitted works.

‘M.R.B.’ contributed two poems to The Inquirer and Commercial News in October and December 1855. They were printed after Charles announced on 26 September that he was available to create compositions. Whether or not they were his work is up for debate. We have no way of knowing whether M.R.B. was a person’s initials (and therefore not Charles) or if it stood for something else. Nevertheless, one poem offers the tantalising possibility that he was the writer.

The first poem, published on 3 October 1855, was called ‘Recollections of Inkermann.’ It paid tribute to the British soldiers who fought at Inkerman (Ukraine) during the Crimean War. The second poem, dated 5 December 1855, was interestingly called ‘The Convict.’ It was that poem that immediately caught my attention.

It tells the story of a convict, his longing for home, and the acceptance that he will never see it again. Faced with a life in chains, the man’s overwhelming desire is for freedom. That desire is only realised with his death by suicide.

There are parallels between the poem and Charles’s life. From the first instance of his incarceration in England in 1850, he tried to escape. In Western Australia, for a brief time, he was a model prisoner. Something changed in 1856. Something or someone was bothering him, and he grew desperate to get his manuscript back. Perhaps it was that overwhelming feeling that resulted in his mistake. There were no second chances. One wrong move, and he was back where he started. For Charles, mirroring the convict in the poem, it seems he felt he had no other option.

Ah! who can tell what anguish reigns, Within that breast, as he exclaims- “In chains then must I die!”

The Convict Dark in the night, the thunders roar; And vivid lightning flashes o'er The blue and mighty deep; There, 'mid howling winds descry Tall cliffs to'wring far on high, Majestic, bold, and steep. Behold a vast, gigantic, rock, Far above the billowy shock Of rushing waters flood, There, reckless of the mighty storm That rages round his manly form, A convict mournful stood. His gaze towards that distant shore, Which he again must ne'er see more, His proud breast beating high; Ah! who can tell what anguish reigns Within that breast, as he exclaims- "In chains then must I die!" He cries - "Shall I no more behold Those dearest haunts, and scenes of old, Where oft I lov'd to roam? No more, alas! my dreams are vain, They're ever gone, and ne'er again For me the joys of home." Upon that rock, so calm, and drear, He sank in calm but deep despair, Exclaiming - "what remains Dear in this world of woe to me, When I'm bereft of liberty, And forc'd to toll in chains." "But no," he cries, "it must not be, Chains ne'er again shall fetter me - Liberty's dear to all; I go; the deep and surging wave Invites me to a peaceful grave, Beneath its watery pall." He rose - and steadfastly gazed on The dashing spray, the stormy foam, And billows' rushing roar; "Farewell false world," he wildly cried, Then plunged into the foaming tide, And sank to rise no more. He plunged, nor paused upon the shore, Ere he had added one crime more To those which stained his fame; He plunged, with unrepenting speed, And lost a worthless life indeed, But left a tarnished name. M.R.B.

Pledge Your Support

Researching and writing stories for The Dusty Box is a labour of love. Unfortunately, it can also be a costly labour of love. While I will always endeavour to have free stories available (history, after all, should be for everyone) if you have the means to do so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $50 for a year - a bargain that equates to just over $4 a month (coffee isn’t even that cheap anymore!). To pledge your support, tap the button below.

Sources:

The National Archives (United Kingdom); Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Class Number: Rg 5; Piece Number: 115

Hertford Mercury and Reformer; 5 October 1850; Volume 16; Issue Number: 845; Page 3; Gale Document Number: GALE|EZ3243424776

Hertford Mercury and Reformer; 14 July 1849; Volume 15; Issue Number: 782; Page 2; Gale Document Number: GALE|EZ3243421940

Hertford Mercury and Reformer; 14 September 1850; Volume 16; Issue Number: 842; Page 3; Gale Document Number: GALE|EZ3243424630

Hertford Mercury and Reformer; 1 March 1851; Volume 17; Issue Number: 867; Gale Document Number: GALE|EZ3243425618

Hertford Mercury and Reformer; 25 January 1851; Volume 17; Issue Number: 861; Gale Document Number: GALE|EZ3243425452

Information about Superintendent Robert Dunn courtesy of Herts Past Policing website (https://www.hertspastpolicing.org.uk/content/crimes_and_incidents/drunk_and_disorderly-4/constable-robert-dunn-the-first-of-many).

The National Archives; Kew, Surrey, England; HO 8: Home Office: Convict Hulks, Convict Prisons and Criminal Lunatic Asylums: Quarterly Returns of Prisoners; Class: HO 8; Piece Number: HO 8/112

Ancestry.com. Western Australia, Australia, Convict Records, 1846-1930[database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Original data:Convict Records. State Records Office of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia. Description: Superintendent Orders, 1850 - 1854 (So1 - So3)Ancestry.com. Western Australia, Australia, Convict Records, 1846-1930 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015.

Original data: Convict Records. State Records Office of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia. Description: Superintendent Orders, 1855 - 1858 (So4 - So6)1855 'Advertising', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 3 October, p. 1. , viewed 30 Nov 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66006488

1855 'Advertising', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 12 December, p. 1. , viewed 01 Dec 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66007126

1856 'Advertising', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 6 February, p. 1. , viewed 01 Dec 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66005749

1856 'Advertising', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 30 April, p. 2. , viewed 01 Dec 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66005007

1856 'Local and Domestic Intelligence.', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 6 August, p. 2. , viewed 07 Dec 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66005540

1855 'Recollections of Inkermann.', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 3 October, p. 2. , viewed 08 Dec 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66006491

1855 'The Concirt.', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 5 December, p. 3. , viewed 08 Dec 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66007207

'The Convict System.—Economy of the Hulks' (1846) Illustrated London News, 21 Feb, 125+, available: https://0-link-gale-com.catalogue.slwa.wa.gov.au/apps/doc/HN3100013862/ILN?u=slwa&sid=bookmark-ILN&xid=f9e8adb5 [accessed 12 Dec 2023].

Parry, J. D. (1827). Select Illustrations, Historical and Topographical, of Bedfordshire: Containing Bedford, Ampthill, Houghton, Luton, and Chicksands. United Kingdom: Longman & Company.

Very good story 👍sad that he died so young 😢

How interesting! I searched through every page on Trove looking for poems, assuming that Charles's work must've been published somewhere if the brief notice of his death referred to it. In the end, only the two I mentioned in the story seemed to fit. I hadn't considered that he may have reviewed other poetry books. It's certainly a possibility it was him! It also matches with the timeline. If you find anything more about Charles, please let me know.