An Albatross's Last Message

A shipwreck, an albatross, and a message.

At 8:30 am, on Sunday, 18 September 1887, five teenage boys left Perth and made their way to North Beach. William Mansbridge, Alfred Moffat, Daniel McCarthy, Edward Bishop, and James Bishop arrived at 11:30 am and were joined by William Walsh. Together, they walked south along the coastline, searching for winkles as they went.

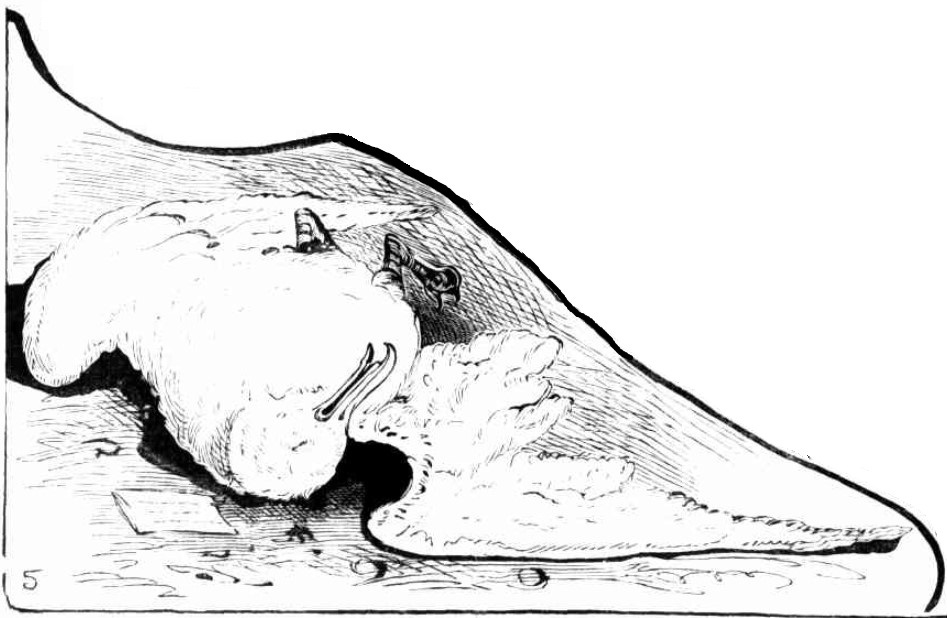

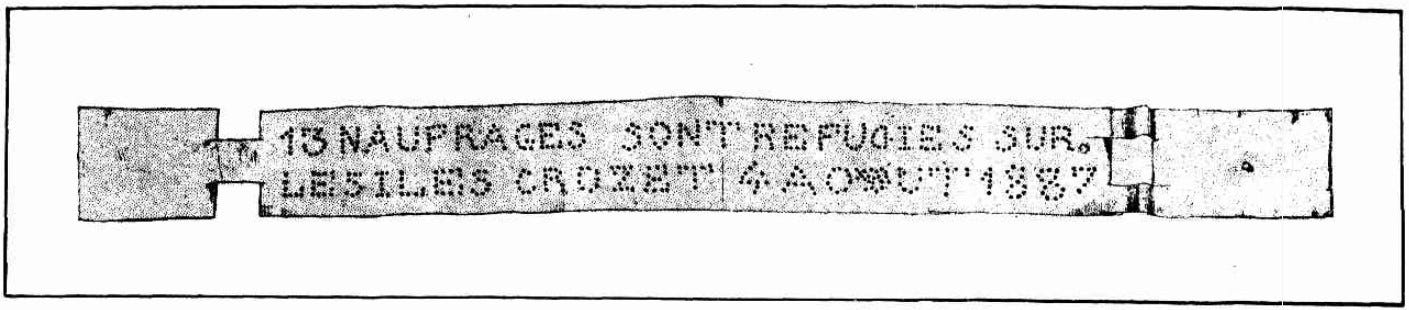

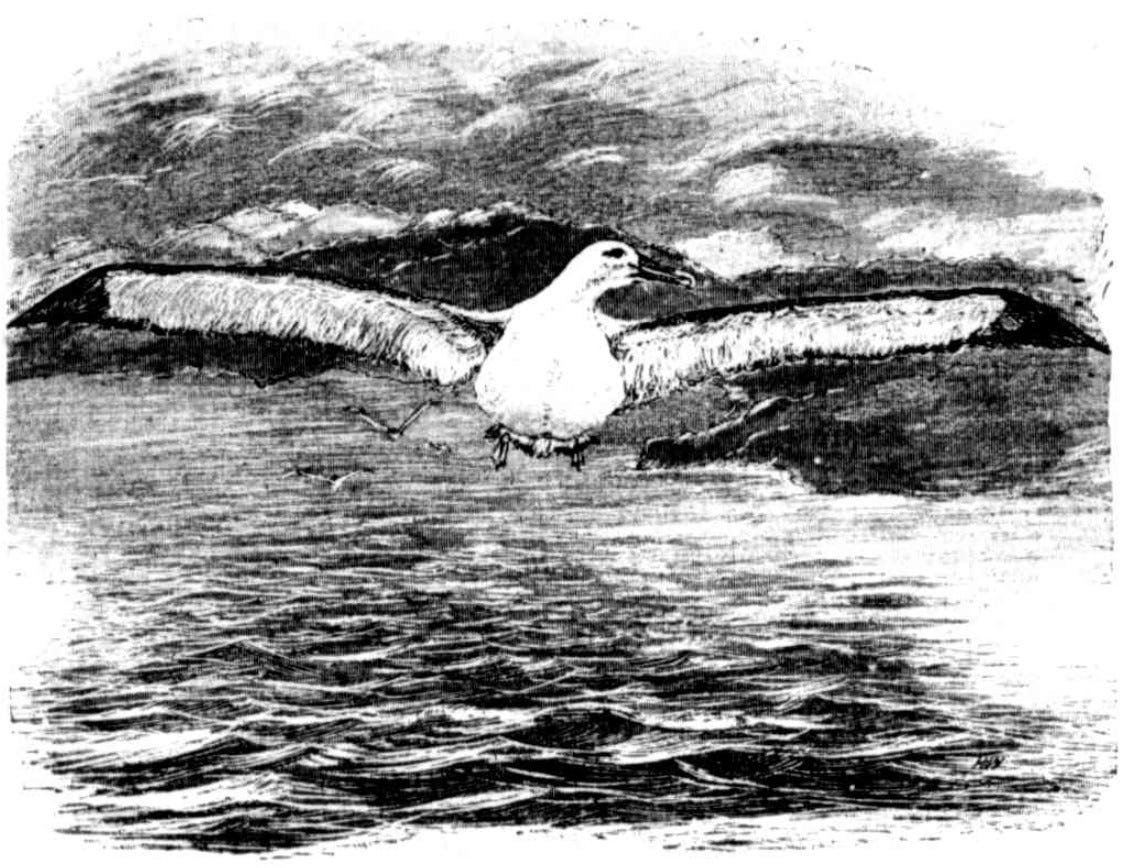

At about 2 pm, four miles south of Trigg Island, they saw a dead albatross washed ashore, just below the high water mark. They picked it up and noticed that fastened around its neck was a tin band about one and a half inches wide and nine inches long. Punctured into the tin were words.

It often happens that strange messages reach land from people in distress at sea, but none could be more extraordinary than that which reached the shores of this colony on Sunday.

The words were French. Unable to understand them and assuming they were unimportant, they removed the tin, and William Mansbridge put it in his pocket. The band had evidently been around the bird’s neck for some time, as there was a rust stain on the feathers when they took it off.

The boys decided to skin the albatross. It bled freely, indicating that it had only recently died. Its stomach was empty, but in its throat were a few mussel shells. Collecting the skin and the wings, they walked back to Perth via the Lime Kilns and Subiaco and arrived at 7:30 pm.

On Monday morning, William gave the tin to John Murphy, a messenger at the Telegraph Office. He promised to show it to the Chief Telegraph Clerk, Henry Clay, who could read French. Henry translated it, and John returned the tin to William, telling him that it said, “Thirteen seamen were wrecked on some islands.” William then handed it to his employer, Vincent Nesbit, who showed it to a reporter at The Daily News and then took it to the Colonial Secretary’s Office.

Translated from French to English, the message read: 13 shipwrecks took refuge on the Crozet Islands 4 August 1887. Once The Daily News broke the story on 19 September, the news of the unusual call for help spread around town. In the background, the Colonial Secretary weighed up whether or not the find was a hoax. He noted within the file: “This is a remarkable occurrence, if it is genuine.”

Sub-Inspector William Lawrence took a statement from Daniel McCarthy on the 20th, and it seems the officials decided to opt for caution. Believing the albatross’s message to be genuine, Governor Sir Frederick Broome sent a telegram to Admiral Henry Fairfax, the Naval Commander in Chief in Sydney.

Albatross found on beach near Fremantle with piece of tin round neck bearing French inscription of which following is translation begins thirteen shipwrecked sailors have taken refuge on the Crozet Islands 4 August 1887 ends. Have discovered nothing to impugn genuineness. Can take no action beyond sending this telegram as seems right to your excellency.

Further telegrams ensued as officials scrambled to figure out what to do. Governor Broome sent a telegram to the Governor of South Australia. The Governor of South Australia responded at 1:49 am on 21 September: “Do you propose telegraphing to the cape [Cape Town] about the people said to be shipwrecked on the Crozets.” The Admiral had not yet responded, and Governor Broome was getting a little impatient. People wanted answers, and he did not know what to tell them. He sent another telegram.

Will your excellency kindly inform me of any action taken on my telegram of yesterday in order that I may reply to inquiries.

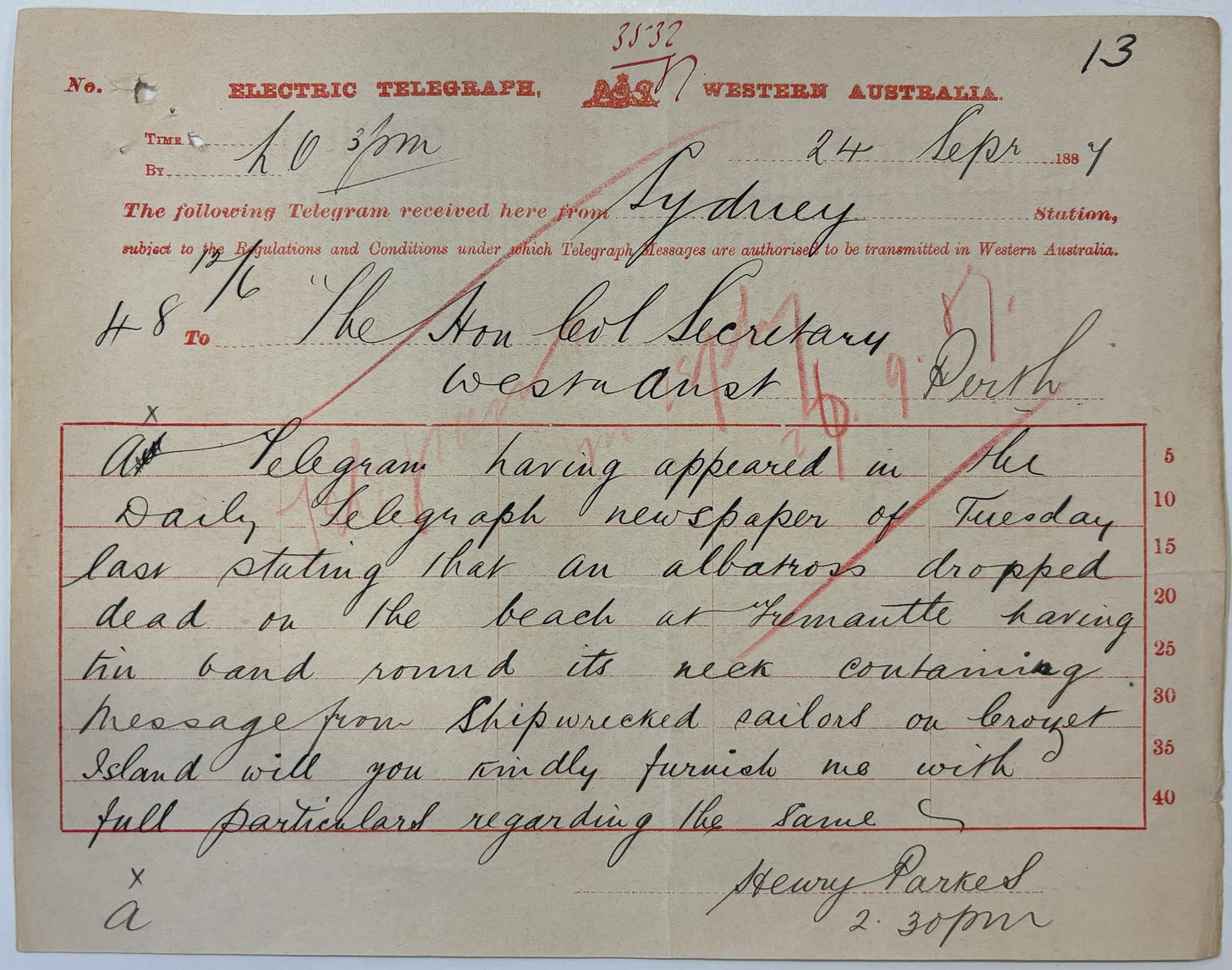

Unfortunately, at that time, Admiral Fairfax was aboard the ‘H.M.S. Diamond’ sailing for Thursday Island. He would not arrive until the 28th, and would not receive messages until that date. In the meantime, the story gained traction across Australia. In New South Wales, George Dibbs (the member for Murrumbidgee) drew attention to it in the Legislative Assembly. Realising its importance, Sir Henry Parkes, the Premier of New South Wales, promised to take action. On 24 September, he sent a telegram to the Colonial Secretary of Western Australia, asking for details.

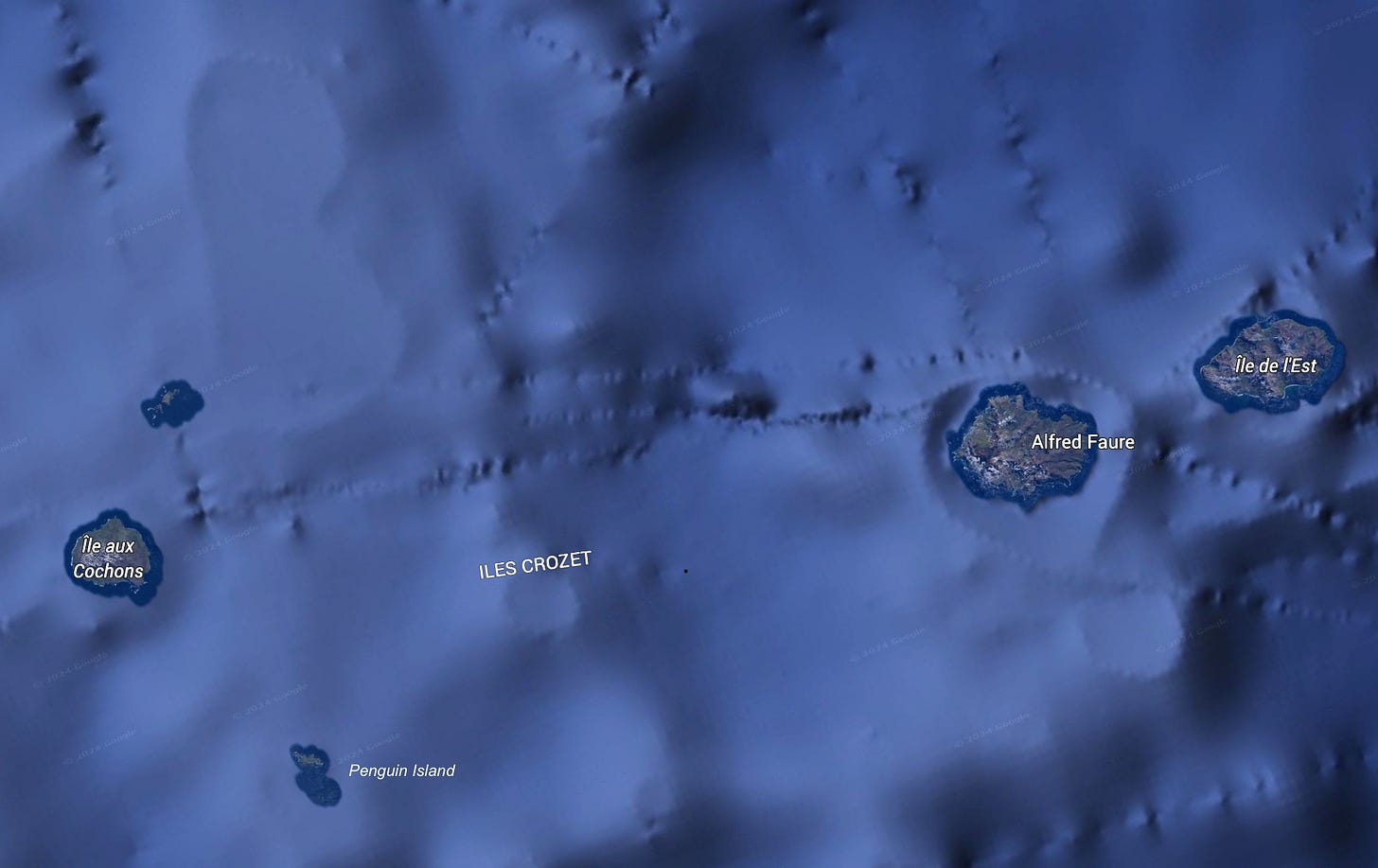

Along with the interest in the story came the inevitable scepticism. The ‘Australasian Shipping News’ labelled it “Another Probable Hoax.” They questioned why the message on the tin band did not include the name of the ship. They were also incredulous at the albatross’s flight. It flew from the Crozet Islands (located 3,127 geographical miles west-south-west from Rottnest Island) in 45 days and died right when people were nearby.

Regardless of the doubt, most people considered it genuine and hoped that the survivors were still alive and that someone would rescue them. There was, after all, a positive circumstance. After the ship ‘Knowsley Hall’ was lost en route to New Zealand in 1879, the New Zealand government proposed establishing a depot of stores on the Crozet Islands, where they assumed the ship had wrecked. When the crew of the ‘Comus’ searched the islands for survivors in 1880, they adopted New Zealand’s suggestion. They built small huts and stocked them with canned provisions for anyone to use if they found themselves in a similar situation. If the French sailors were alive, they would have some food to sustain them.

Finally, on 28 September, Admiral Fairfax returned his messages. His response to Governor Broome was brief: “Have today received your Excellency’s message of 20th & 21st. Thank you for communications & have telegraphed to Admiralty.” The United Kingdom would deal with the matter.

The general public, curious about the action taken by officials to save the sailors, remained oblivious to the machinations of the government offices. While they asked for updates in the newspapers, telegrams were transmitted to England, and letters were forwarded between various officials. On 23 September 1887, John Bramston wrote to the Under Secretary of State, asking him to show Governor Broome’s telegram to Prime Minister Lord Salisbury so that he could communicate the information to the French Government.

On 30 September, a letter was sent to Edwin Egerton (a British diplomat in Paris), likewise asking him to show the telegrams to officials in the French government. In both instances, responses were delayed, and follow-up letters were sent. Finally, on 25 October, Mr Egerton confirmed that he had received a letter from the French Minister of Foreign Affairs. The French Minister had communicated the information to the Minister of Marine and Colonies, and they had commanded that the ship ‘La Meurthe’ be sent to the Crozet Islands “without delay” to investigate.

Back in Australia, the albatross and its message were objects of fascination. Mary Hannay Foott, the editor of the newspaper ‘The Queenslander,’ wrote a poem entitled ‘Washed Ashore.’ In Perth, Vincent Nesbit sensed an opportunity. He exhibited the tin band at the Adelaide Exhibition in November 1887 and then went to Melbourne in December, where jeweller Henry Young and Co. put it on display in their window.

With the French authorities notified, people began speculating on the ship’s name. There was only one possibility. The ‘Tamaris’ departed Bordeaux on 3 December 1886, bound for Noumea. It did not arrive and was listed on Lloyd’s Missing Vessel Register on 31 August 1887. Thirteen men were aboard the ship—the same number noted on the tin.

On 18 November 1887, Lieutenant Richard-Foy sailed ‘La Meurthe’ from Madagascar to the Crozet Islands. They arrived at Crozet’s Hog Island several weeks later and disembarked to investigate. The story was real. The sailors had been living on the island, but they were no longer there.

Commandant - In the first place I have to inform you of the principal object of my voyage, which was to search for thirteen shipwrecked Frenchmen, and to inform you that I am in the unfortunate position of having to return without them.

The crew had left behind a tin box. On the box was a board bearing the words, “Look in the box.” Inside the box was a letter. Signed by Captain Majou, it provided an account of what happened to the ‘Tamaris’, how the crew survived, and the action they took while waiting for rescue.

While en route to Noumea, during a thick mist, the three-masted iron ship ‘Tamaris’ struck a reef near Penguin Island on 9 March 1887 at 2 am. It was able to free itself, but the ship sank south-south-west of the island. The crew escaped in two boats and rowed to Hog Island, reaching it two days later. All they could salvage from the ship was a barrel of water and 300 pounds of biscuits.

Despite being a larger island, Hog Island was just as desolate and isolated. They did not expect to find a hut containing stores, and their reaction to it was one of joy. From 11 March, they remained on the island, ate the canned food, and wore the clothing. They also tried to facilitate their own rescue. Once the cans were empty, they cut strips of the tin and punctured brief messages into them, explaining their situation. On 4 August, one such message was attached to the neck of an albatross before it was set free.

Seven months had passed, and the crew used up the stores provided on Hog Island. On 30 September, about two weeks after the albatross was found dead on a beach in Western Australia, they decided to row to Possession Island. They hoped that they would find a similar hut containing food. Before doing so, Captain Majou wrote his letter and ended it with the following entreaty:

Those who may read these lines are earnestly begged to see whether at Possession Island the unhappy men are still in existence, and to give information of this report to the French Consul of such port as they may next touch at. Hog Island, 30th September, 1887. Signed - P. Majou.

As they had hoped, Possession Island did have a hut similar to that found on Hog Island. Lieutenant Richard-Foy sailed to Possession Island and inspected it. The stores were untouched. He went on to visit all the islands and rocks, but found no trace of the sailors. He presumed that they had either perished during their journey from one island to the other or that another vessel had picked them up.

On 13 December, Lieutenant Richard-Foy sailed back to Hog Island. He restocked the hut with preserved beef, biscuits, cans of sardines, blankets, shoes, trousers, picks, and hatchets. His crew carefully packed everything in 27 cases. His final act was to hang a placard in front of the hut. In French and in English, it said, “These provisions have been deposited by La Meurthe in order to serve the necessities of shipwrecked mariners. Fishermen are begged not to touch them.”

The news of what had befallen the crew of the ‘Tamaris’ slowly made its way around the world, first to France in January 1888, then England, and finally Western Australia in March 1888. An extract of Lieutenant Richard-Foy’s report was published in September 1888.

The tin band remained in Western Australia until May 1890. Whoever had it in their possession decided to sell it. James Clarke (a pearler who once lived in Broome) bought it before moving to Queensland. Mr Clarke stated that he planned to exhibit it on the east coast of Australia, with the proceeds going to charity. He does not appear to have followed through with such claims. Aside from a few reports that the tin is in a museum, its whereabouts today are unknown.

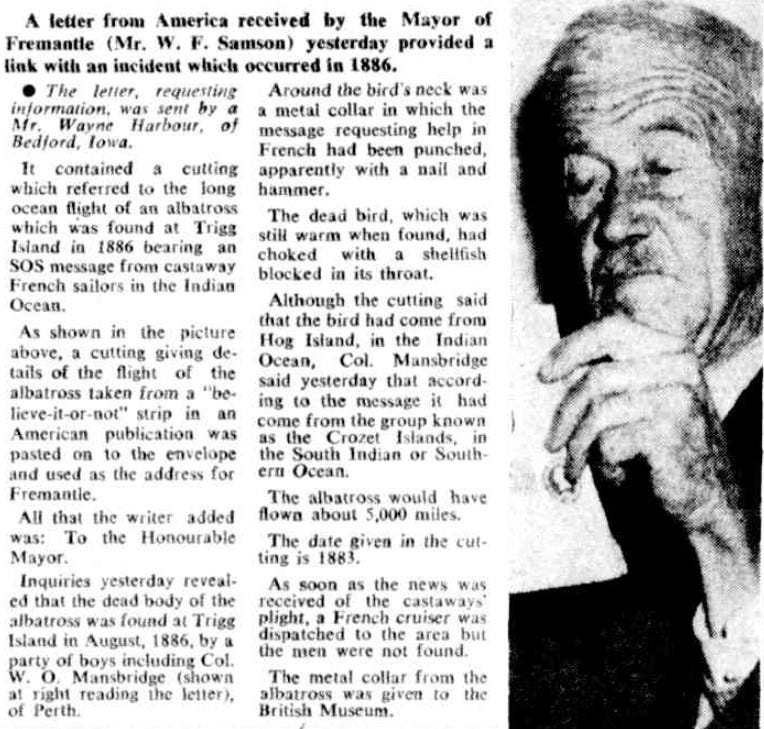

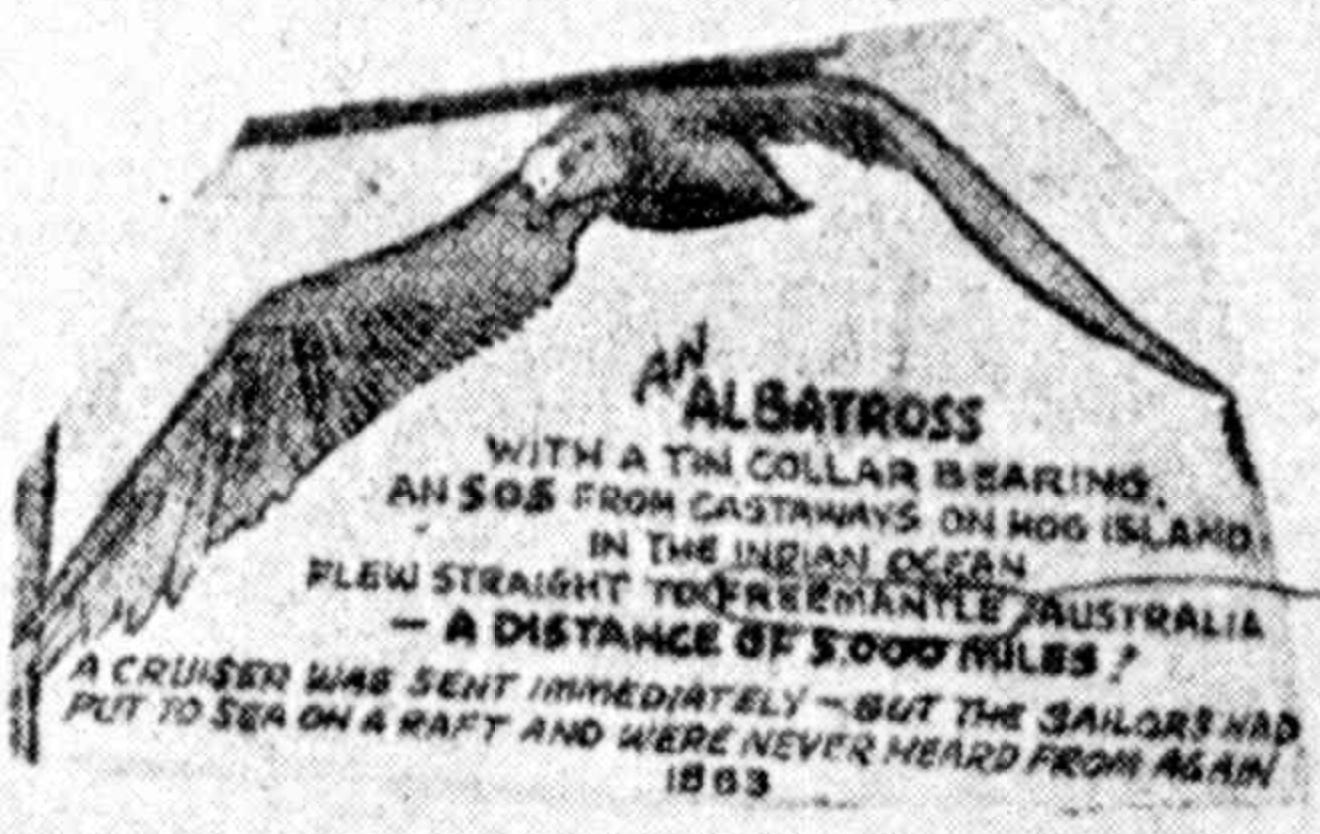

The shipwreck, the albatross, and its last message had captured people’s imaginations. In the decades that followed, various writers referred to the story (albeit with occasional gross inaccuracy). The near-constant retelling indicates the level of interest that its discovery generated in 1887. It had become immortalised in memory. Even an artist drew it for Ripley’s ‘Believe It or Not’ cartoon.

Writers wrote feature articles in newspapers and journals, and, in several instances, clerks granted them access to the Western Australian archival file (the same file that I viewed in 2024). William Hancock, an ex-employee at the telegraph office, accessed it in 1921. A note within the file states that he had also viewed the relevant archival documents in England and France. There was no note detailing his reasons for gathering the information. Perhaps, like me, he was simply fascinated by the story.

In France, the story understandably held even more meaning. The Frenchmen on the ‘Tamaris’ more than likely left behind family and friends to mourn their loss. English-speaking newspapers only printed the captain's name. French newspapers printed the names of the entire crew.

Ajoutons enfin que l’équipage du Tamaris se composait en effet de treize hommes dont voici les noms: Majou, capitaine; Thebaut, second capitaine; Raschieri, maître d’équipage; Casse, charpentier; Fairaud, cuisinier; Courrėge, Ferlicot, Osmont, Rousseau, Le Bouffaut, Magre, L’Epinard, matelots; Robin, mousse.

Finally, let us add that the crew of the Tamaris was in fact made up of thirteen men whose names were as follows: Majou, captain; Thebaut, second captain; Raschieri, boatswain; Casse, carpenter; Fairaud, cook; Courrėge, Ferlicot, Osmont, Rousseau, Le Bouffaut, Magre, L’Epinard, sailors; Robin, apprentice.

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands commemorated the story. In 1995, they issued a stamp showing the albatross in flight in front of the ‘Tamaris.’ In 2021, it was again commemorated. The new stamp depicted ‘La Meurthe’ sailing on its rescue mission to the Crozet Islands.

The story had all the elements of tragedy: a dark, misty morning, a shipwreck, an escape, survival, hope, and an unusual call for help that, while successful, did not result in the desired outcome. It was that ingenious call for help—a piece of tin pierced with a message and attached to the neck of an albatross—that garnered the most attention. It was the albatross’s flight, thousands of miles across the Indian Ocean, to land (and sadly die) at the right spot for the boys to find it—that seems as incredulous now as it must have been back then. And it was the persistence of the story. Long after 1887, it lived in people's memories and attached itself to those who were involved. It was told and retold. It is impossible to resist such a story, and I've now (inevitably) added my own version to the mix.

Pledge Your Support

Researching and writing stories for The Dusty Box is a labour of love. Unfortunately, it can also be a costly labour of love. While I will always endeavour to have free stories available (history, after all, should be for everyone) if you have the means to do so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $50 for a year - a bargain that equates to just over $4 a month (coffee isn’t even that cheap anymore!). To pledge your support, tap the button below.

Sources:

State Records Office of Western Australia; Colonial Secretary’s Office; Sydney - French Shipwrecked Sailors on Crozet Islands, Re; AU WA S675- cons527 1887/3532

'SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE' (1887) Aberdeen Journal, 01 Sep, available: https://0-link-gale-com.catalogue.slwa.wa.gov.au/apps/doc/BA3205782093/GDCS?u=slwa&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=9fd4a5f4 [accessed 31 May 2024].

1887 'LETTERS TO THE EDITOR.', The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1955), 24 September, p. 3. , viewed 02 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76474470

1887 'REMARKABLE MESSAGE FROM THE SEA.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 20 September, p. 3. , viewed 09 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3760893

1887 'NEWS AND NOTES.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 21 September, p. 3. , viewed 09 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3761873

1887 'THE MESSAGE BY THE ALBATROSS FROM THE CROZETS.', The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1955), 27 September, p. 3. , viewed 09 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76473510

1887 'SHIPPING REPORT.', The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 - 1901), 12 October, p. 4. , viewed 09 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66081255

1887 'THE MESSAGE OF THE ALBATROSS.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 20 October, p. 3. , viewed 09 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3114244

1887 'THE MESSAGE of the ALBATROSS.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 21 November, p. 3. , viewed 11 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3114901

1887 'THE CROZET ISLES REFUGEES.', The Pictorial Australian (Adelaide, SA : 1885 - 1895), 1 November, p. 16. , viewed 24 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article225065914

1887 'EVENTS OF THE WEEK.', Melbourne Punch (Vic. : 1855 - 1900), 29 September, p. 6. , viewed 24 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article174572508

1887 'LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY.', The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), 22 September, p. 3. , viewed 27 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13658678

Foreign Office Records; Shipwrecked French sailors on Crozet Islands. French consul at Melbourne. Diplomatic; http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-937082968

Foreign Office Records; French shipwrecked sailors on Crozet Islands. Diplomatic; http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-936331599

Foreign Office Records; French in New Caledonia. Crozet Island. Diplomatic; http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-936999174

Foreign Office Records; French shipwrecked sailors on Crozet Islands. Diplomatic; http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-937389176

Foreign Office Records; French shipwrecked sailors on Crozet Islands. Diplomatic; http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-937387895

1887 'Brevities.', Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 - 1931), 9 November, p. 6. , viewed 30 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108230737

1887 'FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 1887.', The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), 9 December, p. 7. , viewed 30 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article7878863

Anon (1883) COLLINS-STREET IMPROVEMENTS - MESSRS H. YOUNG AND CO.’S NEW PREMISES. [picture]. Melbourne: David Syme and Co.

1887 'THE SHIPWRECKED PERSONS ON THE CROZETS.', The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), 22 November, p. 8. , viewed 30 May 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13671566

Lloyd's Missing Vessel 1885 - 1889. (1885). (n.p.): Lloyd's Register

Le Soleil (1873-1922); 26 Decembre 1887; p. 3/4

1888 'THE MESSAGE FROM THE SEA.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 6 September, p. 3. , viewed 06 Jun 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3120618

1880 'LONDON TOWN TALK.', The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), 14 August, p. 4. , viewed 06 Jun 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5953203

1890 'NEWS AND NOTES.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 21 May, p. 3. , viewed 07 Jun 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3134351

1894 'The Albatross.', Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1919), 15 December, p. 19. , viewed 07 Jun 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71267401

1953 'LETTER FROM U.S.A. RECALLS 1886 INCIDENT', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 23 May, p. 12. , viewed 11 Jun 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article55805928

Le XIXe siècle; 18 October 1887; Page 3/4

Why did they skin the albatross?🤔

Very good 😊 did they find sailers?