The beginning of a story inevitably starts with a birth. Thomas Tolhurst was born circa 1863 in Gilton Town Ash, England, to Thomas Tolhurst and Sarah Davison. He was the eldest of eight children, including his younger brother Stephen. His early years show him recorded on the 1871 and 1881 England Census as living at Sturry and then Chatham, both in the county of Kent.

A person may have many reasons for immigrating. In this instance, we can only speculate. For Thomas, the death of his father (a stonedresser) in 1884 may have had some kind of influence upon him. By the late 1880s, he was living in Victoria. In 1888, he married Augusta Phillips.

Thomas and Augusta (also known as Annie) were living in rural Victoria when Augusta fell pregnant. Their daughter, Lillian Evelyn (registered as Lillias Emeline in the Victorian Births, Deaths, and Marriages database), was born in 1889 in Southern Cross, Victoria.

The years together as a family were brief. On 14 November 1891, Augusta died in Cobden. A widower and perhaps uncertain about his and Lillian’s future in Victoria, Thomas turned his attention to the west. His younger brother Stephen had been living on the Western Australian goldfields since at least 1892. Reuniting with family may have made the decision easier.

Thomas and Lillian moved to Western Australia between 1891 and 1895. He took up land near Moora and called the farm Clivevale. He was not the sole owner of the property. On 28 October 1895, he entered into a partnership with his brother, Stephen, and Harry Kallawk. There was no official contract. The agreement was verbal.

The columns of The West Australian provide us with tiny glimpses of Thomas’s life in Moora in the early 1900s. On 15 May 1903, he served on the committee for the bachelors’ ball held in the Moora Agricultural Hall. On 8 September 1906, he was elected to the committee of management for swine for the Moora Agricultural Show. A month later, a return ball was given by the married residents for the bachelors. The night ended with ‘Messrs. Tolhurst’ and Frank Brown giving a speech thanking the organisers.

Thomas and Harry Kallawk lived on the farm and shared the work. Despite his financial interest, Stephen Tolhurst was mostly absent. He was recorded in the 1905 electoral roll as living at Clivevale, but soon after, it appears he went back to the goldfields.

On 10 August 1907, the Western Mail published photographs and information relating to farms in the Midlands districts. A short paragraph on Clivevale described it as being 1,600 acres located about four miles from Moora. Thomas had cleared and cultivated four hundred acres and averaged 18 bushels to the acre. The reporter noted that Thomas “arrived from South Australia about 14 years ago.”

The launch of the newspaper The Midlands Advertiser in 1907 resulted in additional references to Thomas. From these references, we can paint a picture of a man who not only worked hard on his farm but also actively participated in the community.

On 7 September 1907, he attended a public meeting at Moora to discuss the possibility of the government purchasing the Midland Railway Line. He was open to listening to the other settlers’ opinions and was willing to support the movement if it benefited the “small settler.”

In December, a meeting was held at Clivevale with the purpose of forming the Mocarramarra Cricket Club. The group established a men’s and women’s team, with Lillian Tolhurst agreeing to be the secretary for the women. They played regular cricket matches and often enjoyed afternoon tea at the Tolhurst’s home.

On 1 January 1908, a fire swept through the Moora district. It started in a paddock two miles from the town and moved west when the wind changed. Several farmers lost feed, while Thomas was noted to be a “heavy loser.” The fire destroyed two stacks of hay, a shed, 400 acres of feed, and two miles of fencing.

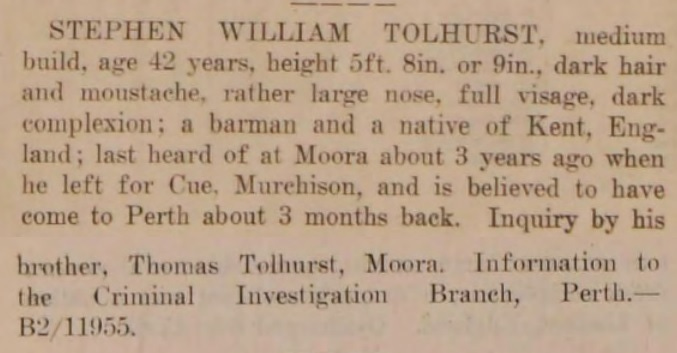

At that time, Thomas had not heard from Stephen for years and did not know where he was. It may have been the damage caused by the fire that forced him to track his brother down. All he knew was that around 1905, Stephen left Moora for Cue and was somewhere on the Murchison goldfields. Unable to find him on his own, Thomas contacted the police.

On 6 May 1908, a ‘missing friends’ notice was placed in the Western Australia Police Gazette. Unbeknownst to Thomas, Stephen was living near Sandstone, and on 9 January 1908, he had partnered with Samuel Holden and Sidney Page in a mining lease at Youanmi called ‘Boulder North.’ By June that year, the police printed a confirmation in the gazette that they had found Stephen at Sandstone. Whether he returned to Moora is unknown.

On 10 October 1908, Thomas hosted a social at Clivevale in honour of the Batt family, who were moving to Hill River. He gave a speech, wishing his old neighbours success on their new farm. He highlighted the respect he felt for them and expressed regret at losing “such worthy neighbours and genuine farmers.” He provided refreshments, and everyone who attended had a “jolly evening” dancing until daylight.

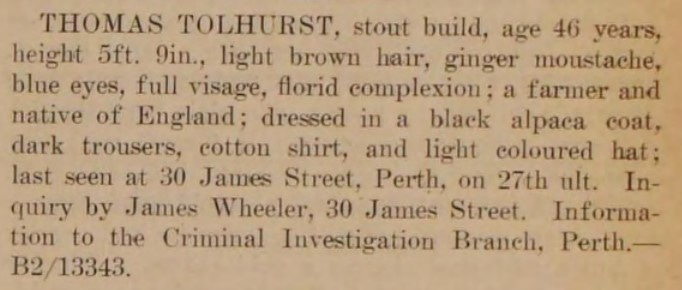

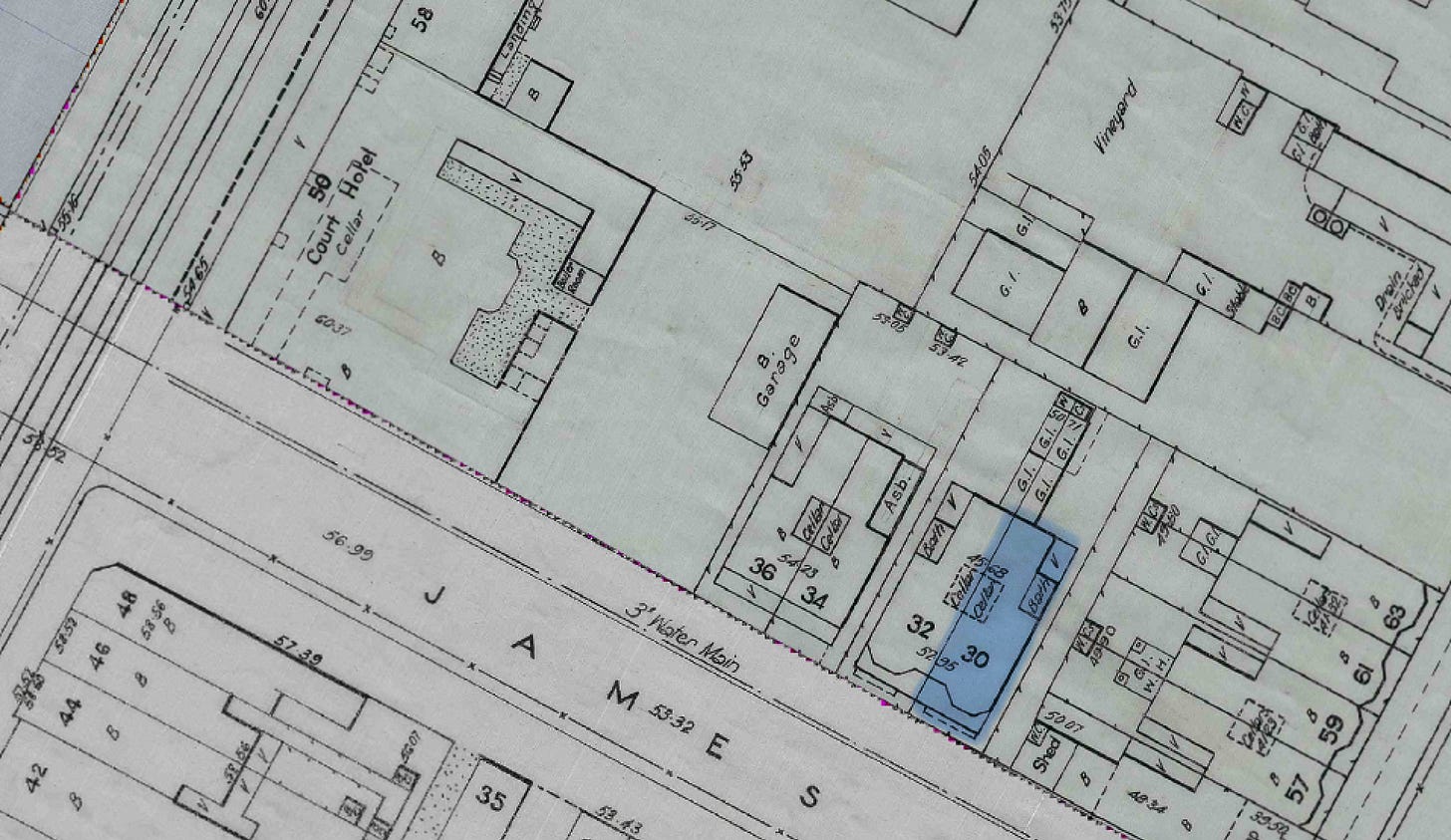

On 24 February 1909, Thomas travelled from Moora to Perth via train for business. He stayed with Frederick and Elizabeth Wheeler at their home on 30 James Street. On 5 March, The Midlands Advertiser published a list of goods and parcels awaiting collection at the Moora Railway Station. Among the names listed was ‘T. Tolhurst.’ Thomas did not arrive to collect the goods, and on 7 March 1909, he was declared missing.

A report filed with the Western Australian Police started the process of trying to find him. A missing person notice was placed in the next police gazette, and details slowly made their way into newspapers. Thomas was last seen on 27 February, and was wearing a black alpaca coat, dark trousers, a cotton shirt, and a light coloured hat.

On 15 March, The West Australian published more details about Thomas’s “peculiar disappearance.” They listed his movements in Perth at the end of February: his visit to the bank and his successful loan application, and the fact that he told Mrs Wheeler on the 27th that he was “going into town to keep an appointment with a gentleman.” Thomas was described as having “methodical habits.” That meant his disappearance was out of the ordinary and was considered “shrouded in mystery.”

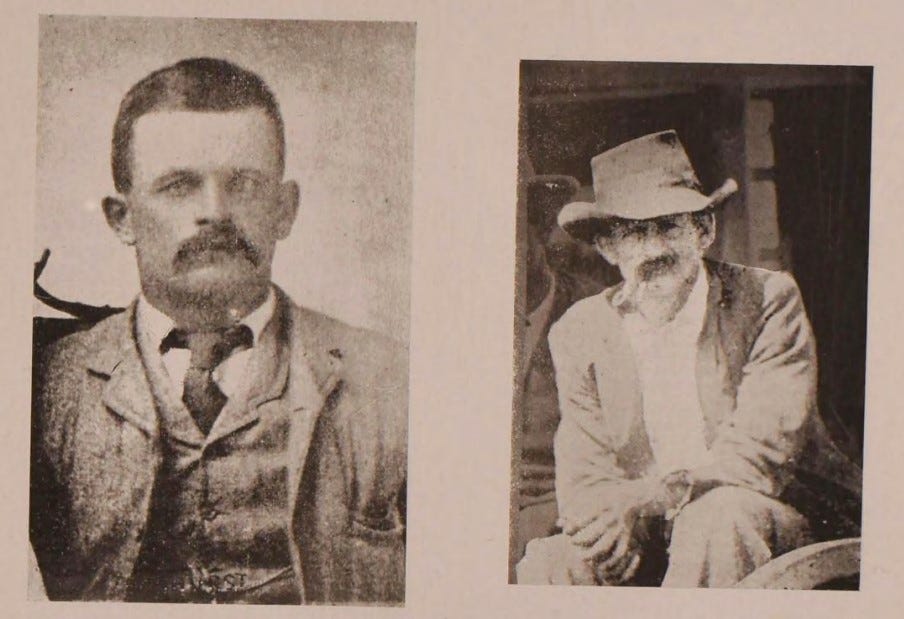

The details in the newspapers throughout the rest of the month were scant. On 28 March, the Sunday Times published a photo of Thomas, and on 31 March, the police escalated his disappearance to a ‘Special Inquiry.’ To aid with their inquiries, two photographs of Thomas were printed in the police gazette.

The Criminal Investigation Branch assigned the case to plain-clothes detective Aubrey Lamond. In early April, he visited Moora and New Norcia and questioned various people about Thomas’s disappearance. The Midlands Advertiser reported that “nothing could be learned” and Detective Lamond returned to Perth.

On 5 April 1909, The West Australian reported that despite inquiries, the police had found no trace of Thomas Tolhurst. Having become acquainted with more details of the case, they explained his movements throughout February.

At the start of the month, Thomas left Moora, travelled to Perth, and successfully raised a loan with his bank. He paid away a portion of it, returned to Moora, and deposited the balance in his bank account. He kept a small amount in his wallet for expenses. On 24 February, he left Moora and again went to Perth for business. He stayed, as he always did, at 30 James Street. The last day he was seen (the 27th), he complained about the heat, mentioned that he had an appointment, and said he would return in the afternoon. He missed the appointment, and the gentleman he was supposed to meet (said to be his solicitor, Richard Hourigan) waited over an hour before leaving.

Facts and the supernatural intertwined. Thomas’s daughter, Lillian, was in a state of panic. She resided at Clivevale and, along with her friends, had done everything she could to try to find her father. She was also engaged to be married. In her anxiety, and on the advice of a friend, she consulted a clairvoyant. The clairvoyant went into a trance and described Thomas and their farm in Moora. They then dropped a bombshell. Thomas had been murdered and was buried in the bush close to the city.

While they could not pinpoint the exact location, they stated that the person who would find the burial place was a man who lived in a house with an old, dilapidated sign out the front. A few days later, two men were riding in the bush three miles from South Perth when they came across recently disturbed sand. Sulky tracks led to the area. Curious, they started to dig. They reached about a foot below the surface when they stopped. There was a terrible smell coming from the hole.

The men told their story to their acquaintances, and it eventually reached the ears of Lillian’s friends. At their insistence, the men contacted the police. Detectives visited one of them at his home in South Perth. When they arrived, they saw a dilapidated sign out the front. On 29 March, he showed them the place in the bush. The police, eager to follow any lead, decided to dig it up.

Armed with a shovel and a nerve-steadying bottle of brandy, the detective, guided by the South Perth horseman, got to the spot by 8 o’clock.

They kept digging until they reached the object. It was not Thomas, and it was not human. It was the decomposing remains of a calf.

Rumours of sightings of Thomas were printed in the newspapers but never confirmed. He was reportedly seen at Bunbury on 28 February and stayed there until 11 March. He left, indicating that he was next going to Sandstone. Unable to verify whether or not it was Thomas, police had no other option than to suspect foul play.

News dried up in the months that followed. On 25 June 1909, Lillian Tolhurst married Harry McNamara at St George’s Cathedral in Perth. A little over a month later, her name was listed alongside her father’s in an advertisement placed in The West Australian. Harry Kallawk and Stephen Tolhurst applied to the Supreme Court to have the partnership between the three men declared to have existed. They also sought its dissolution.

The case was heard at the Nisi Prius Court on 13 October 1909. Justice Rooth recognised that the partnership had existed for years without a written agreement, but he refused to dissolve it. Seven months passed before the next hearing, and Thomas’s disappearance remained shrouded in mystery.

…the intimation that T. Tolhurst was the man who disappeared some time ago opened the doors to the whiff of mystery, and the court temperature went down to a ghostly frigidity.

On Friday, 13 May 1910, Justice Rooth again heard the case for the dissolution of partnership. Richard Hourigan represented Harry Kallawk and Stephen Tolhurst. Robert Robinson represented Lillian, Thomas’s sole beneficiary.

Mr Hourigan explained to the court that even though Lillian was the sole beneficiary, she could not do anything about her father’s Estate until seven years had passed since he disappeared. It left the partners in a quandary. By rights, each person was entitled to their share. Dissolving the partnership was paramount.

By that point, Stephen had decided that he wanted to take over the entire interest in the partnership. He had already approached Harry, who sold his third share to Stephen for £500. There was only Thomas’s share left, and Stephen was anxious to buy it. He offered Lillian £500 and payment of her costs in connection to the court application. Lillian accepted the offer.

Despite Thomas’s absence, the court did not forget about his rights. Mr Robinson stated that Stephen had agreed that if Thomas returned within the next seven years, he would let him back into the partnership. Furthermore, he suggested the court should hold the £500 until either Thomas returned or seven years lapsed. Justice Rooth agreed. He dissolved the partnership and vested the £500 in the Master of the Supreme Court.

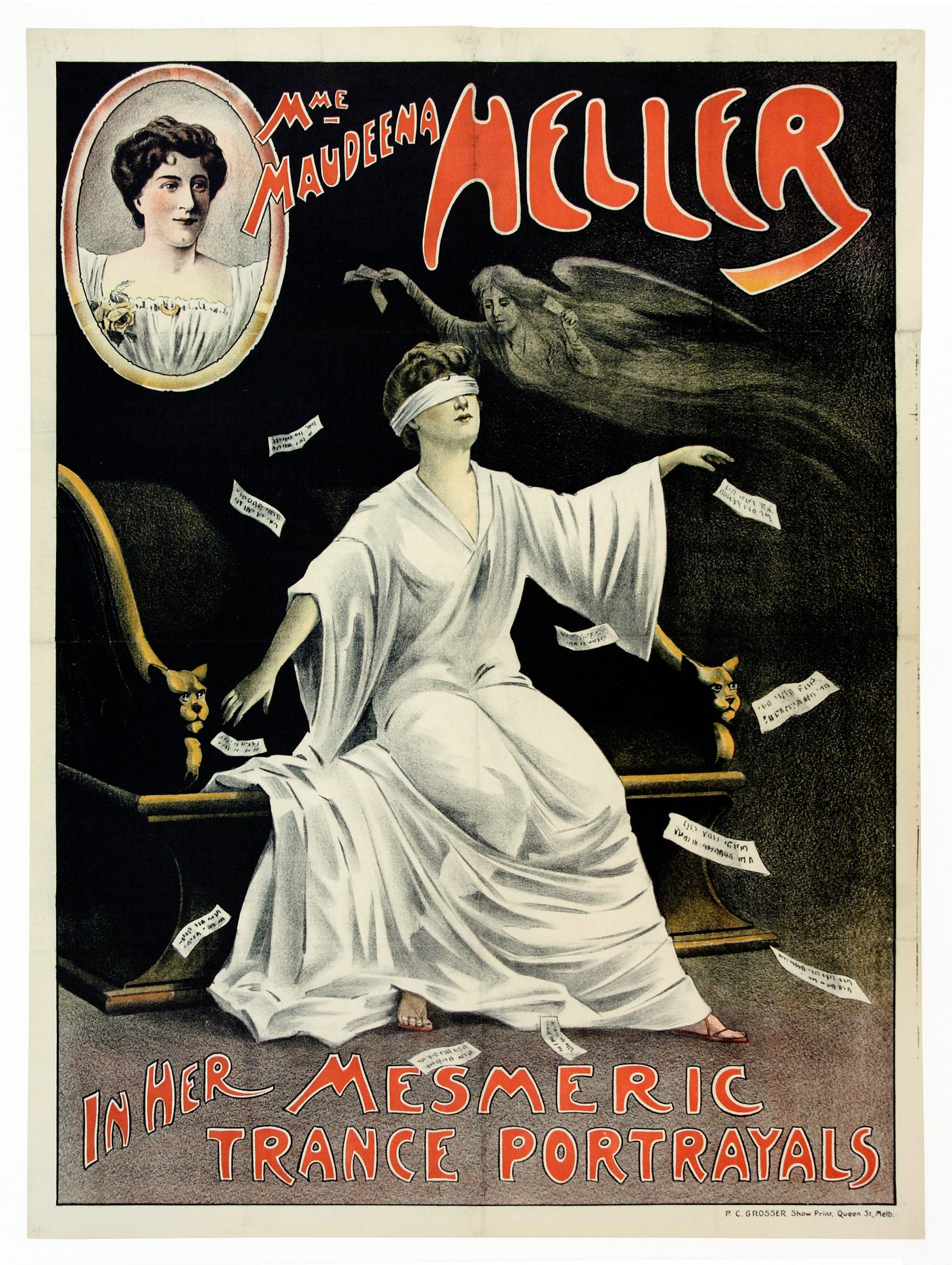

In late July 1910, Professor Heller and Madame Maude Heller announced they were touring Western Australian towns to perform “mystical novelties, clairvoyancy, and spiritualistic manifestations.” Four years had passed since their last tour, and one of the first towns they visited was Moora.

At some point (more than likely while they were at Moora), they became aware of the strange disappearance of Thomas Tolhurst. From Moora, they travelled to Geraldton, where they performed at the Town Hall on 4 August. During that show, Madame Heller claimed that Thomas had moved to Canada, changed his surname to Wheeler, and was farming about seven miles from Toronto.

Life slowly resumed without Thomas. Lillian lived at Moora with her husband, Harry, and their first child, who was born in 1909. Stephen also continued living at Moora. As the sole owner of the property, he was free to do with it as he liked. In May 1911, he sold part of the Clivevale estate, the stock, and the machinery to Joshua Waldeck for £3,472. It appears he sold another part to Charles Ferguson in about October 1912.

On 1 July 1913, Charles Herbert Spargo was hanged at Fremantle Prison for the murder of Gilbert Pickering Jones in Broome. The case became known as ‘The Mangrove Mystery’ and featured heavily in the newspapers. Solving it involved painstaking detective work by the Western Australian Police, one of whom was Aubrey Lamond.

While Spargo was hanged for one murder, the police believed that he may have been responsible for many others. In the weeks that followed, detectives invited a reporter from The West Australian to discuss that possibility. They showed them clothing that may have belonged to a man who was missing and explained how it connected back to Spargo. Inspector John Walsh made a passing remark that “the mysterious disappearances of Jones and Dickerson were not by any means the only cases of their kind in this State.” He gave one name as an example: Thomas Tolhurst.

The Sunday Times, a little miffed at being left out of the loop, provided their own detailed article. They claimed that a correspondent wrote to them about Thomas Tolhurst’s disappearance, stating that it “bears a striking resemblance to the several mysteries which Spargo is said to be concerned with.”

The reporter also had additional information about the Bunbury sighting. As it turned out, it was Thomas Griffith, the licensee of the Burlington Hotel, who recognised Thomas’s photo in the newspaper. He said that Thomas arrived in Bunbury on 28 February, stayed at the Burlington until 11 March, and then departed for Perth on the midnight train.

Even if it was Thomas in Bunbury, what became of him once he returned to Perth continued to be speculative. The reporter for the Sunday Times theorised that upon his return, he may have visited horse bazaars in the city–places that Spargo was known to hang around and formed part of his modus operandi.

Those competent to judge think it likely that Spargo found an unsuspecting victim in Tolhurst, and having enticed him to a lonely spot on some pretext, there murdered him.

While intriguing, there was, they admitted, no evidence that Spargo played any part in Thomas’s disappearance.

As Thomas did not have a Will, seven years after he disappeared, Lillian applied for Letters of Administration for his Estate. It is in those documents that a clearer picture of his final days emerges, but it leaves us none the wiser as to what happened to him.

On 3 February 1909, Thomas travelled from Moora to Perth to obtain a loan to purchase property. He was successful and returned home on 22 February, depositing £356 into the National Bank at Moora, which was the balance out of the loan money. When Lillian saw him, he was “in the best of health and spirits.”

A few days later, on 24 February, he again travelled to Perth to apply for another mortgage of £500. He carried £5 on his person, about £1 of which he used to pay for his train ticket. As he always did when he was in Perth, he stayed with the Wheelers at 30 James Street.

On 27 February (the last day he was seen), he had breakfast, left the house, and returned at lunchtime. He ate his meal and complained about his head troubling him. He left the Wheeler’s house at 2:30 pm. He did not say where he was going. It was the last credible sighting of Thomas.

The police confirmed that there were rumoured sightings of Thomas at Bunbury, Moondyne, Quadailing Station (possibly meant to be Quaraiding), Fremantle, New Norcia, Southern Cross, and Toronto. Their inquiries could not ascertain whether any of those sightings were of Thomas or of someone else entirely.

Around the time of Thomas’s disappearance, his mother, Sarah, was staying in Chester County, U.S.A. with her daughter, Rosa. The police also contacted her, but she was unable to help. She had not heard from Thomas either.

Nothing has been seen or heard of the said Thomas Tolhurst since that time nor has any reason been given for his disappearance.

The Supreme Court declared that Thomas Tolhurst was presumed to have died on 27 February 1909. Lillian was the sole beneficiary and inherited the £500 that the court had held since 1910.

There was, so far as anybody could judge, no reasons why he should vanish of his own intent, either by travel or suicide in some unrevealable fashion.

The disappearance of Thomas Tolhurst is one of those puzzling stories that raises more questions than answers. Would he leave Western Australia without telling anyone? Among the Estate documents was a copy of an affidavit from Harry Kallawk. In it he swears that “Thomas Tolhurst had never been absent from the said partnership property on any prior occasion without informing me of his movements.”

Thomas twice travelled to Perth to apply for loans. He was in charge of the partnership’s business dealings and bank accounts. When he could not find his brother in 1908, he contacted the police. He was a man who acted in consideration of others. It seems unlikely that he would leave and purposely cause distress to his family and friends.

Did he have an accident? There are two references to Thomas not feeling altogether well. He complained about the heat. He complained that his head was bothering him. Perhaps he died suddenly due to a medical episode. If that were the case, surely someone would have discovered his body. The fact that no one found it increases suspicion that he was a victim of foul play.

In 1913, when discussing Charles Spargo and his victims with a reporter, Inspector Walsh chose to mention Thomas’s name. There was no confirmation that he was one of Spargo’s victims, but it nevertheless gives us a tiny clue regarding the detectives’ theories. They did not think Thomas left on his own accord. Placing his name alongside Spargo’s was a statement in itself.

After his retirement, Inspector Harry Mann shared his policing stories, including how they caught Spargo. Spargo was the “known killer of one man” and the “suspected killer of three more.” No one saw those three men again. Inspector Mann was direct. As long as they remained missing, he would “keep calling Spargo a mass killer.”

Spargo left no confession, so his involvement (if any) in Thomas’s disappearance remains speculative. The police and the public’s search for Thomas revealed nothing. He was not in another country. His remains were not found. No one knew what had happened to the Moora farmer. On 27 February 1909, Thomas Tolhurst left the house on James Street and simply vanished.

Pledge Your Support

Researching and writing stories for The Dusty Box is a labour of love. Unfortunately, it can also be a costly labour of love. While I will always endeavour to have free stories available (history, after all, should be for everyone) if you have the means to do so, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $50 for a year - a bargain that equates to just over $4 a month (coffee isn’t even that cheap anymore!). To pledge your support, tap the button below.

Sources:

State Records Office of Western Australia; Supreme Court of Western Australia; Applications for Grants of Letters of Administration (Originals); Thomas Tolhurst; AU WA S59- cons3458 1916/181

1903 'SOCIAL NOTES.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 21 May, p. 5. , viewed 03 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article24824216

1906 'MOORA AGRICULTURAL SHOW.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 14 September, p. 6. , viewed 03 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25688519

1906 'SOCIAL NOTES.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 31 October, p. 4. , viewed 03 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25692325

1907 'IN THE MIDLAND DISTRICTS.', Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 - 1954), 10 August, p. 6. , viewed 04 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37810691

1907 'IN THE MIDLANI DISTRICTS—SOME PROSPEROUS HOMES. (See Farm.)', Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 - 1954), 10 August, p. 28. , viewed 04 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37810789

1907 'The Midland Line.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 27 September, p. 1. , viewed 05 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156501456

1907 'Cricket.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 6 December, p. 2. , viewed 05 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156501222

1907 'Mocarramarra Cricket Club.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 13 December, p. 3. , viewed 05 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156501547

1908 'Notes and Comments.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 7 February, p. 5. , viewed 05 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156501592

1908 'Advertising', Mount Magnet Miner and Lennonville Leader (WA : 1896 - 1926), 11 January, p. 3. , viewed 05 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155861779

1908 'Notes and Comments.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 16 October, p. 4. , viewed 05 Sep 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156503760

Western Australia Police Gazette; 6 May 1908; No. 19; Page 121. Courtesy of the State Records Office of Western Australia.

Western Australia Police Gazette; 17 March 1909; No. 11; Page 71. Courtesy of the State Records Office of Western Australia.

Western Australia Police Gazette; 31 March 1909; No. 13; Page 83. Courtesy of the State Records Office of Western Australia.

1909 'Railway Manifest.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 5 March, p. 5. , viewed 04 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156503897

1909 'THE MISSING FARMER.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 15 March, p. 7. , viewed 04 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26223164

1909 'No title', Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 - 1954), 28 March, p. 3. (FIRST SECTION), viewed 04 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57611175

1909 'FRIDAY, APRIL 9, 1909.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 9 April, p. 4. , viewed 04 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156504425

1909 'THE DISAPPEARANCE OF TOLHURST.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 5 April, p. 7. , viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26224919

1909 'NEWS ITEMS.', Murchison Advocate (WA : 1898 - 1912), 10 April, p. 2. , viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213888078

1909 'Family Notices', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 2 July, p. 1. , viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26231830

1909 'Advertising', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 11 August, p. 1. , viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26234841

1909 'NEWS AND NOTES.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 14 October, p. 5. , viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26239789

1910 'MAN WHO VANISHED.', The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1955), 13 May, p. 4. (THIRD EDITION), viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77823916

1910 'A MYSTERIOUS DISAPPERANCE.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 14 May, p. 9. , viewed 10 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26257151

1910 'TELEGRAMS.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 29 July, p. 4. , viewed 14 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156508703

1910 'Local News.', Geraldton Guardian (WA : 1906 - 1928), 6 August, p. 2. , viewed 14 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66288493

1911 'FRIDAY, MAY 26, 1911.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 26 May, p. 4. , viewed 15 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156512205

1912 'MOORA ROAD BOARD.', The Midlands Advertiser (Moora, WA : 1907 - 1930), 4 October, p. 4. , viewed 16 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article157076907

1913 'ON THE MISSING LIST.', The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), 15 July, p. 8. , viewed 16 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article26879678

1913 'SPARGO AND DICKERSON', Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 - 1954), 20 July, p. 6. (First Section), viewed 16 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57749836

1952 'HE MADE A BUSINESS OF MURDER', Mirror (Perth, WA : 1921 - 1956), 5 January, p. 9. , viewed 22 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75784768

1903 'AN EXEMPIARY SCHOOLBOY.', Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 - 1954), 14 November, p. 26. , viewed 24 Oct 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article37378907

Dear Jessica I love your blog, and your research in finding unusual stories is exactly what I love doing too. thanks so much, Louise

Interesting story and by all accounts seems the fella succumbed to foul play, a lot easier to get away with in those early days.